Early exposure cuts confusion

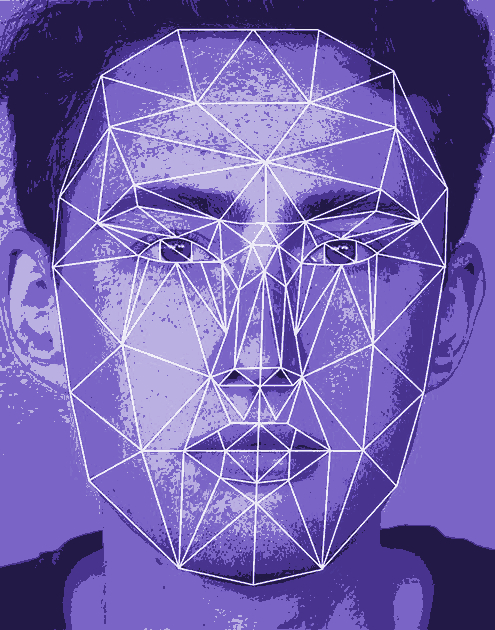

A diverse upbringing could help us better recognise faces across different races as adults.

A diverse upbringing could help us better recognise faces across different races as adults.

A recent study at the Australian National University examined the ‘other-race effect’, a phenomenon in which people have difficulty telling apart individuals of a different race to their own.

It found social contact during childhood can reduce and even eliminate much of the effect.

Dr Amy Dawel said it is an important finding.

“The other-race effect can have serious real-world consequences,” Dr Dawel said.

“For example, inaccurate cross-race eyewitness testimony has contributed to wrongful criminal convictions, passport misidentifications and even magazines mistakenly illustrating stories with a picture of the wrong person.”

The study asked participants how much contact they had with people from other races during primary school, and then as adults.

Those who had more contact during primary school had less difficultly recognising faces across different races as adults.

Interestingly, adolescent and adult contact had little impact.

According Dr Dawel, this suggests there may be a critical window during which our human face recognition system is shaped.

“Our results suggest that exposing children to faces of different races during childhood will help reduce the other-race effect,” Dr Dawel said.

“It is possible that people could still learn to recognise other-race faces better later on in life, but it would be like learning a second language as an adult.

“It would take most of us a lot of practice and time, and we might never become ‘fluent’.”

The researchers believe there could be good reason for the parallels between facial recognition and language acquisition.

“Our findings match up with the well-known critical period for language acquisition,” said co-author Associate Professor Evan Kidd, who holds a dual role with ANU and the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics in the Netherlands.

“Both language and faces are important for communication - we focus on the face when speaking and listening, and both faces and voices help us identify individuals and members of our social group.”

The team is now working on developing new training methods to reduce the other-race effect in adulthood.

The research has been published in the journal Scientific Reports.

Print

Print