Brain probe questions posed

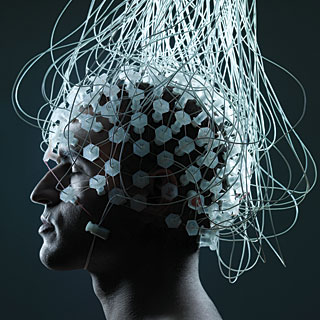

Experts have reflected on the ethics of brain-monitoring technology.

Experts have reflected on the ethics of brain-monitoring technology.

As technology advances, it is possible that an ankle-bracelet for criminal offenders could be replaced by some sort of brain-bracelet.

Dr Allan McCay, a criminal law scholar at University of Sydney Law School, has published the first substantial overview of neurotechnology and its implications for the law and the legal profession.

Neurotechnologies are technologies that interact directly with the brain, or more broadly the nervous system, by monitoring and recording neural activity, and/or acting to influence it.

Sometimes neurotechnology is implanted in the brain but it may also be in the form of a headset, wristband or helmet.

The technology is already being used in health settings for the treatment of patients with Parkinson’s and epilepsy and could be used in the future to monitor and treat schizophrenia, depression and anxiety.

But the same technology could potentially be used for the brain monitoring of criminal offenders or for cognitive enhancement, creating a divide between enhanced and non-enhanced humans.

It could also be used to monitor workplaces, used by the military (cyborg super-soldiers), used for gaming and perhaps as a means of interacting with the metaverse.

“This tech is coming, and we need to think about regulation now,” says Dr McCay.

“Action is needed now as there are already vested interests in the commercial world. We need decisions to be made at the level of society and at the level of businesses around ethics and law.”

The report puts forth some serious legal and ethical questions, including;

-

Could a brain-bracelet be worn externally to their skull by criminal offenders to track their thoughts? Or implanted like a pacemaker?

-

Could brain-bracelets monitor impulsive thoughts and deliver interventions?

-

Could a criminal claim their brain was hacked?

-

Could thoughts become criminal acts if they lead to a physical crime? How would this be sentenced?

-

Could a court order that your brain be monitored at all times?

-

If brain-monitoring systems store data, who is going to control that data and where might it go?

-

Do we have a right to brain privacy? Will there be a loss of mental privacy to corporations and perhaps states? Governments might want to predict how we behave as predictions become more accurate.

-

Could lawyers become cognitively enhanced and have their brains monitored for attention by their firms?

-

Could there be other legal profession issues? Instead of billable hours, could the way lawyers charge one day be by way of “billable units of attention” and might neurotech change the way lawyers compete with each other?

-

Might lawyers try to compete with AI systems employed in legal work by making use of neurotechnology?

“This tech is coming, and we need to think about regulation,” said Dr McCay.

“Action is needed now as there are significant neurotech investors such as Elon Musk and Meta (Facebook).

“We need law reform bodies, policy makers and academics to be scrutinising these technological advances rather than waiting for problems to emerge.

“To take criminal law as an example, numerous questions emerge. One might ask which bit of conduct constitutes the actus reus (criminal act) where a person injures another by controlling a drone by thought alone.

“It seems easier to identify the relevant conduct where the defendant uses their system of musculature to control the drone by manually manipulating a controlling device such as a joystick.

“Moving to sentencing, would it be acceptable for criminal justice systems to monitor and perhaps even intervene on offenders’ brains by way of a neurotechnological device while they are serving sentences in the community?

“This latter question of course raises human rights concerns and there is now an important debate as to whether existing human rights protections are fit for purpose give the possibility of brain-monitoring and manipulation.

“The human rights issues extend well beyond the criminal law into other areas of law,” he said.

The full report is accessible here.

Print

Print