Approaching the pointy-end of icicle mystery

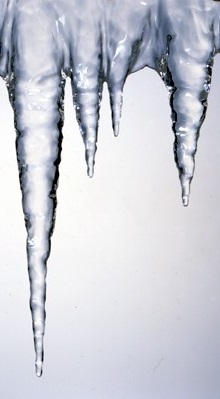

As you may or may not have noticed, icicles have ripples of exactly the same wavelength no matter how big they get. Scientists are now trying to work out why.

As you may or may not have noticed, icicles have ripples of exactly the same wavelength no matter how big they get. Scientists are now trying to work out why.

“As far as we know it's the same everywhere in the world,” says Professor Stephen Morris of the University of Toronto,

“The fascinating part of it is that they're always found to be the same wavelength. It's very hard to explain why there's ripples at all, and it's even harder to explain why they don't change.”

Prof Morris is one of several authors of a study which has begun to solve the rippling riddle.

A paper published by the New Journal of Physics says small impurities in the water may be a contributor.

The researchers found that pure, distilled water forms icicles with no ripples whatsoever.

“Only icicles made from slightly salty or dirty water formed ripples, so it turns out to be an impurity affect, which was completely unexpected,” Morris says.

Further investigation revealed salt may be the key.

“We controlled all the temperatures, and all the flow rates, and we can stir the air or make it windy... the only thing that makes a real difference for the ripples growing, was the saltiness... we know as you add more salt, they grow faster and get larger, so we know the salt is necessary.”

But as is often the case in science, new information only leads to more questions.

“We don't really know why, and we don't have a very good explanation for the wavelength of the ripples,” Prof Morris says.

“We changed the surface tension by adding soap, but that wasn't enough to produce ripples... the next thing is to try different kinds of salt, and different kinds of soap, combinations of salt and soap. We're also working on the theory but that's not complete yet.”

Sheer curiosity is rarely enough to get funding these days, but the scientists say that is what has driven them. There are genuine applications for their findings though, with the build-up of ice and icicles creating serious hazards for power lines, ships, bridges and aircraft, among others.

“This is what we call blue sky research. we're curious about anything we see in nature that occurs regularly and needs an explanation... science is really about curiosity and just being curious is quite motivating and interesting,” Morris said.

Print

Print